The Evolution of Friendship Park

Photos © Aryana Noroozi

Beginnings

Patricia Nixon inaugurates Friendship Park on August 18, 1971. Photo © National Archives and Records Administration

Friendship Park was inaugurated by First Lady Patricia Nixon on August 18, 1971.

The park stretches from the Pacific Ocean across a mesa a half acre long. It straddles the border between the United States and Mexico. Friendship Park is binational, its circumference embraces Imperial Beach, California and Playas de Tijuana, Baja California, Mexico. Reports of that 1971 summer day focussed not only on the new park but Nixon’s reaction to the land itself. “I hate to see a fence here,” Nixon said as she ventured to find a break in the wall to step across to Mexico. It’s not likely the First Lady or anyone else celebrating the new park that day, would have predicted the space would become a flashpoint for tension at the border and immigration policy decades later.

The park is situated in the most southwestern point in the U.S.. The land originally belonged to the federal government as a navy training facility. Since the late 1950’s San Diego wildlife conservation activists petitioned for the land to become a national park. In 1971 it was gifted to California’s Department of Parks and Recreation and the construction of Border Field State Park began.

Nixon was crusading for Legacy of the Parks, an initiative to expand the nation’s parks and outdoor spaces. Friendship Park was her final stop on the tour. After stepping through what was then a barbed wire fence and walking into Mexico she greeted many people. “Esta bueno,” said a woman watching from a distance.

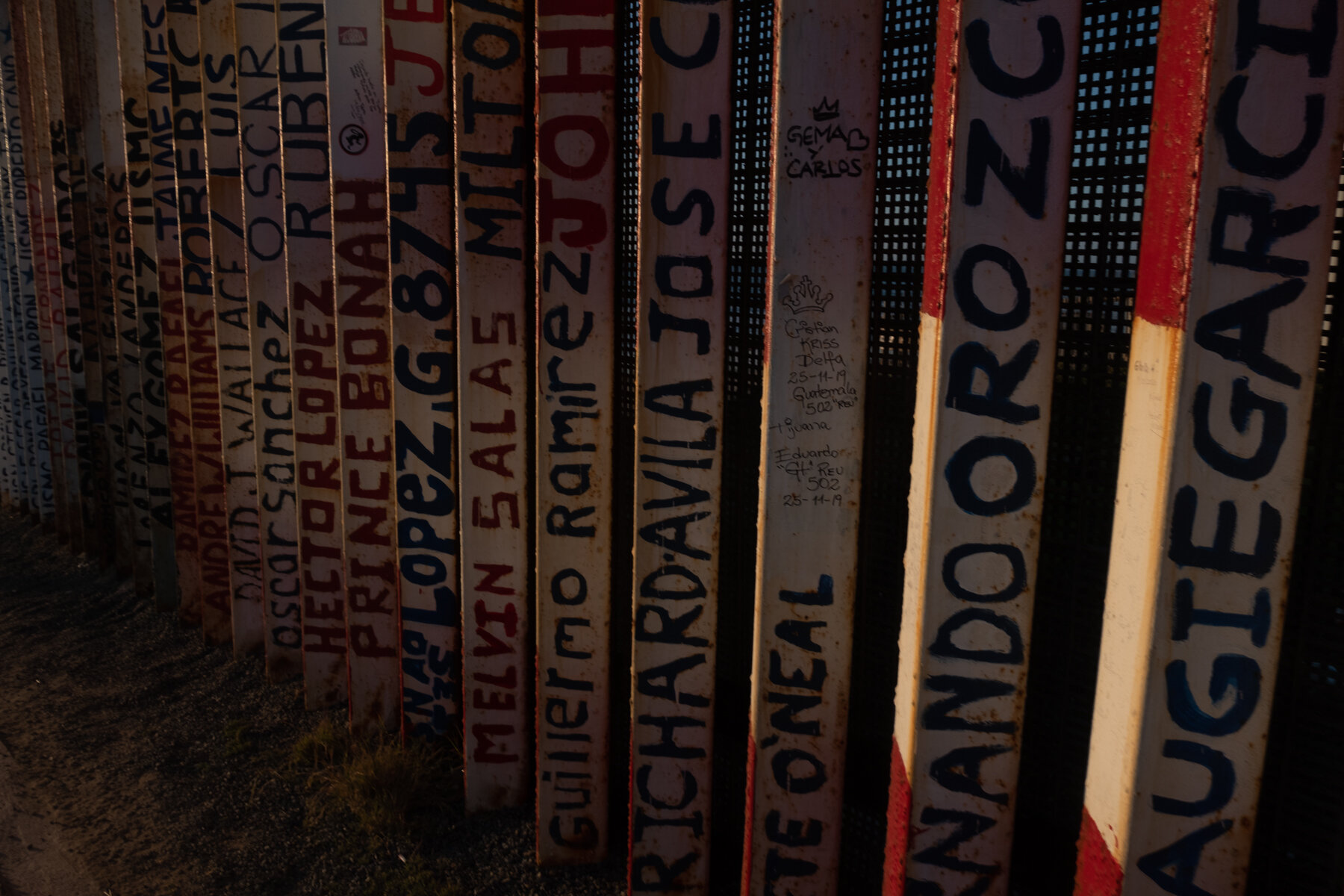

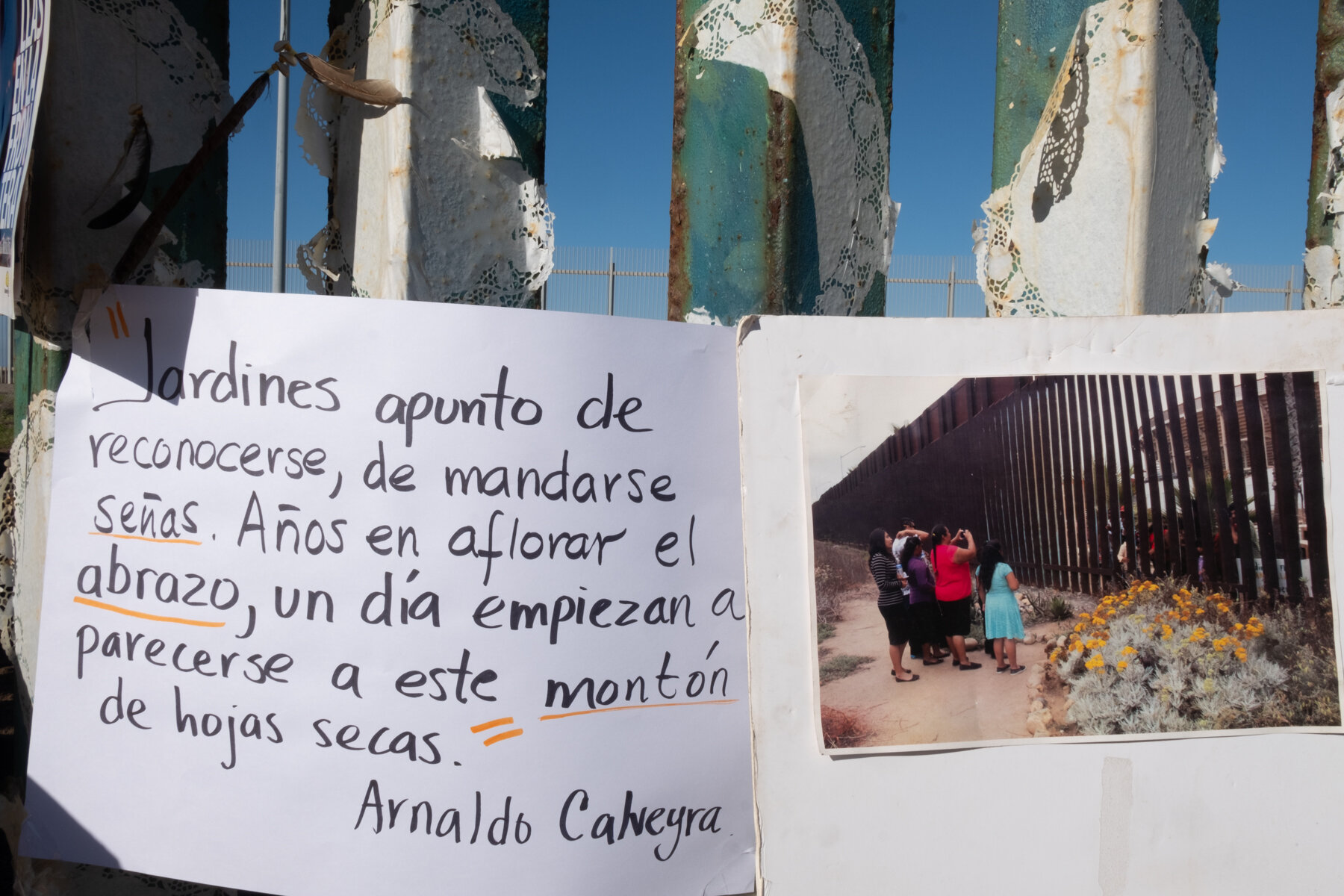

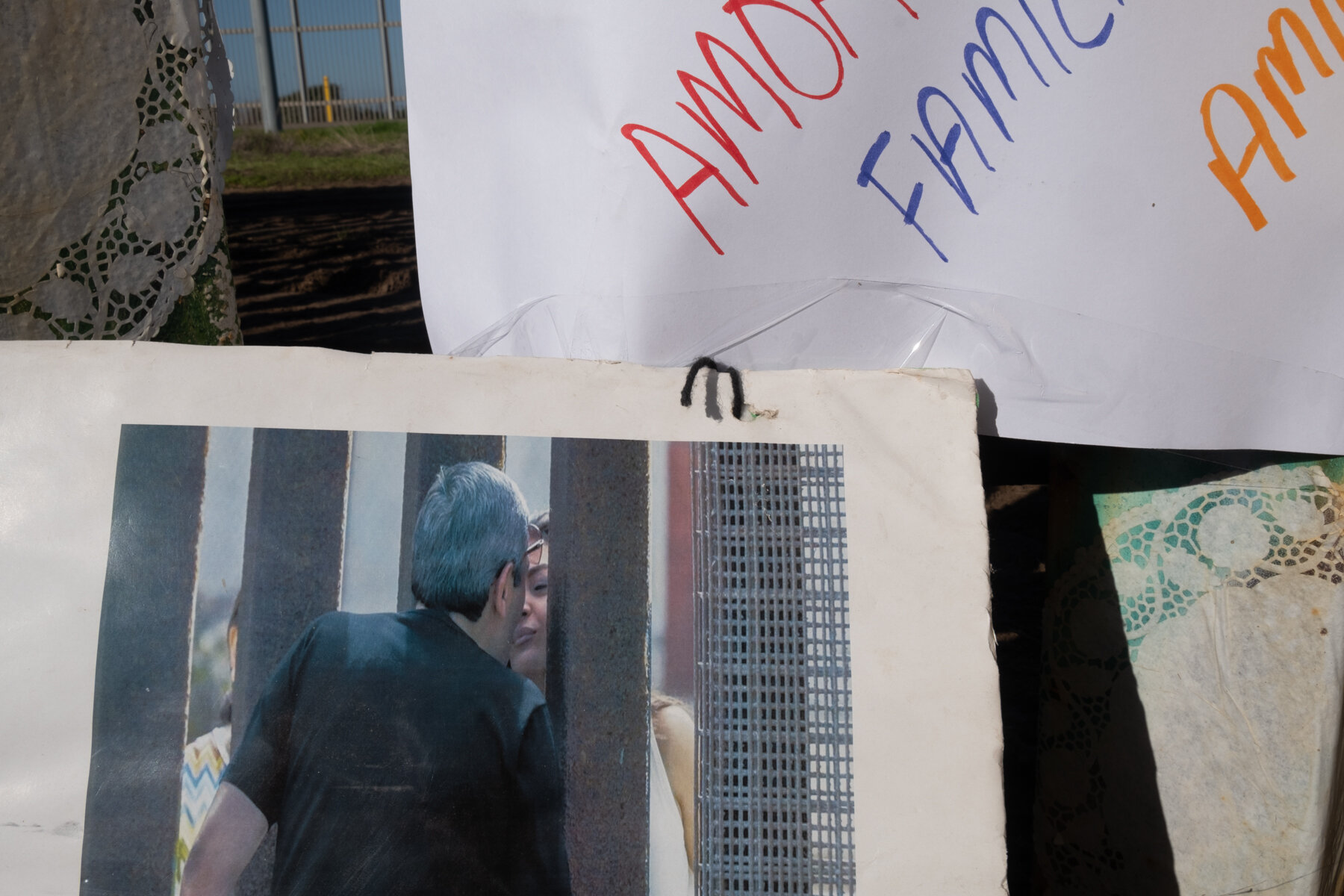

Friendship Park or Parque de la Amistad served as a meeting point for binational interactions for decades. Loved ones separated by border policy often met at the park to share afternoons together. Prayer services, yoga lessons and poetry readings were among the different gatherings people could enjoy through the wall at Friendship Park. Until 1994, a chain link fence - which allowed people to touch and see each other - separated the two countries. This began to change in 1994 under Operation Gatekeeper, an initiative that ramped up border security and enforcement of illegal immigration. As the border fence continues to be fortified with a triple layer fence and the Trump Administration pushes for stronger and additional walls, the ability to connect at this half-century-old meeting place diminishes.

Friendship Park serves as a physical representation of changes in border policy over the past forty years. The concept of building a wall came in 1990 when President George H. Bush approved 14 miles of fencing in the San Diego sector, and has grown under the Trump Administration. Orders from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security eroded environmental regulations in 2005 by launching the construction of a 13-mile wall. The new wall not only placed a physical barrier in Friendship Park, but also a barrier in the lives of its community. Despite those changes, the park continues to serve as a place of worship and reunification.

The interactive timelines below chronicle changes in both Friendship Park and border policy, and demonstrate how these changes affected the migrant population.

Hyperlinked sourcing for above timelines can be found here.

To some, Friendship Park is a way to communicate with their family on the other side of the border. On the U.S. side, visitation regulations established in 2012 allow for a maximum of 10 people at one time to enter the park between 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. on weekends. Visitors must show proof of documentation and recently, are not allowed to bring chairs or strollers during the visits. The park once allowed for touching through what once was a chain link fence. At times, Border Patrol agents would open the gate so visitors could fully embrace. Now only pinkies are allowed to touch through the thick mesh fence that towers over 15 feet high. Friendship Park goers call this a pinkie kiss.

Pinkie kisses given at the end of a Border Church and Border Mosque interfaith service on December 22, 2019. Photo ©Aryana Noroozi

Two Homes in One Park

For Robert Vivar, 64, Friendship Park has been a place of refuge and acceptance. It’s helped him cope with and embrace his life after deportation.

(Right and left) Robert Vivar sits on his in balcony in his home, the very last apartment next to the international border in Playas de Tijuana, Baja California, Mexco. Photo ©Aryana Noroozi

(Middle) Robert Vivar watches the U.S. garden replanting through the border wall. Photo courtesy of Jardín binacional de amistad/Binational Friendship Garden.

Vivar was born in Tijuana but came to Corona, California legally when he was six years old. He was the only member of his family not born in the U.S. and was on the legal path to citizenship. For more than forty years of his life, Vivar lived in Corona. He worked in the airline industry as an AeroMexico airport manager at LAX and later climbed the ranks to a regional manager for Taesa Airlines. Vivar helped launch offices in Las Vegas, Chicago, Detroit and Oakland. In 1996, Vivar began to experiment with drugs, became addicted and could no longer work in the airline industry. He was arrested and pleaded guilty to a possession charge that he said unbeknownst to him was a trafficking and deportable charge. Vivar was deported in 2003. He was 47. After months of being unable to find work in Mexico, Vivar came back to the U.S. undocumented. In the passenger seat, he arrived at the San Ysidro international border with his Boston Redsox cap. After his driver responded to the border patrol agent’s questions about the weekend in Mexico, Vivar, with only a California driver's license, was waved through to the U.S.. For the next ten years he worked and lived in Corona, undocumented. Eventually immigration officials caught up to Vivar, resulting in an eighteen month stay in a detention center. There he fought his deportation order up to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals. After losing his case, Vivar was deported for his second time in 2013. He found himself in Playas de Tijuana.

“I felt like my life was over, like I had nowhere to go. Just completely lost in a place that I didn't know,” Vivar said.

Vivar eventually found work at an American car rental company call center and became an activist.

Listen below to a preview of Vivar’s story and what Friendship Park means to him.

Planting the Seeds of Friendship Garden

In the early 2000s, Daniel Watman, a Spanish teacher at Mesa Community College in San Diego, began taking his students to Tijuana for a day. He wanted students to experience the Latin culture a few miles south. In the summer of 2004 when Watman’s school administration refused to give him approval, he got creative. Watman was also a volunteer lifeguard at Playas de Tijuana. He asked his colleagues from the lifeguard tower in Mexico if they would come to their side of Friendship Park and meet his students on the American side. There, the group was able to speak through the wall for hours. “The thing I like so much about bringing my students to Tijuana is that their idea of what a Mexican is just melts away,” Watman said.

Portrait of Daniel Watman in January 2020. Daniel protesting construction of the wall shortly before he was arrested for doing so in February 2009. Photos courtesy of Jardín binacional de amistad/Binational Friendship Garden.

“When people get to know each other as individuals they broke through a barrier and I think doing it through an actual barrier made them want to break through it even more,” said Watman.

Friendships formed as a result of those conversations. The exchange also inspired Watman to organize more events at the park. He formed Border Encuentro, a series of events that identified common interests and fostered joint participation on both sides of the fence. Activities included language exchanges, poetry readings and yoga. During the next two years, Border Encuentro held up to twenty events a year.

In 2007, Watman created the Binational Garden or Jardín Binacional to promote the idea of friendship and native flora blossoming through the border wall. Growth did not always come easily to the garden though. As the timeline indicates, the garden suffered under the 2009 park closure and Watman was detained for attempting to garden. In January 2020, Border Patrol bulldozed the garden without notice. Agents claimed they meant to trim the plants on the U.S. side. A few weeks later, Watman and other volunteers were allowed to replant, but the garden had to be set four feet back from the wall because border patrol agents believed that smugglers were using it to cross.

Faith at Friendship Park

On December 21, 2019, Congresswoman Rashida Tlaib visited Friendship Park to meet with deported U.S. veterans and parents. Tlaib attended the interfaith Border Church and Border Mosque worship service.

Listen below to hear Tlaib speak about the border wall.

Congresswoman Rashida Tlaib meets with deported veterans during her visit to Friendship Park in Playas de Tijuana, Baja California, Mexco. Photos ©Aryana Noroozi

Friendship Park Galleries

Photos ©Aryana Noroozi or as otherwise noted in timelines